No one should be punished for defending themselves against domestic violence.

And yet, across the United States, it is the horrific practice of prosecutors to criminalize survivors of sexual and intimate partner violence for self-defense. According to the Defend Survivors Now campaign by abolitionist organization Survived and Punished, 90 percent of incarcerated people in women’s prisons are survivors of sexual or domestic violence. While this statistic is based on post-conviction data, bail review hearings highlight how this pattern occurs at the pretrial level—and Baltimore is not an outlier.

In April of this year, Judge Jeannie Hong followed a recommendation from the State’s Attorney’s Office and ordered a survivor to be held without bail, despite the trauma she had already faced from her abusive partner. Now, this person has another abuser: the state. And the survivor is even more unsafe. This intentional withholding of safety is compounded for queer, trans, and gender non-conforming survivors. According to Love & Protect, an organization supporting criminalized survivors of violence, from the conception of this country, Black women, trans people,, and gender-nonconforming people have been continually punished for self-defense because “the system does not believe [they have] a life worth saving.” This practice started with settler-colonization and chattel slavery more than 400 years ago, when Black people

in North America were denied personhood and the right to even have a self to defend.

According to abolitionist educator and organizer Mariame Kaba in the booklet “No Selves to Defend,” in 1913, a Black woman named Mary Wilson was caged in Texas for defending herself against white- and gender-based violence. In 2010, a Black woman named Marissa Alexander was caged for defending herself against her abusive ex-husband in Florida. Despite no physical harm caused by Alexander, a jury found that the same “stand your ground” laws that protected George Zimmerman did not apply to her.

In the case of the survivor held without bail in April by Hong, her day in court will not be until at least the middle of 2023. This means she will be locked up—for defending herself—for more than a year before she even goes to trial. She has children that need their mother. But because she is in jail, she has been separated from her family. Because she is in jail, custody of her kids goes to their abusive father. Because she is in jail, both she and her children are unsafe.

In Baltimore City Circuit Court, all bail review decisions are made based on perceived flight risk and public safety. Black women and gender-nonconforming people are consistently determined by prosecutors to be a “public safety risk,” and caged.

That determination is often based on police statements, despite the Baltimore Police Department’s extensive and documented criminal history. This decision is made with no requirement to consider the safety of the survivor or the violence inflicted on them—from their abuser and the state. By determining that a survivor is a danger to others for acting in self defense, the state makes them separate from the public, and thus undeserving of safety. So survivors sit in jails and prisons while abusers—including cops and prosecutors—are protected.

Despite a “progressive” façade, the State’s Attorney’s Office does little to prevent domestic violence—they only come into the picture after violence has already occurred, and often use their discretion to prosecute survivors who act in self-defense. If the criminal-legal system protected survivors, sexual- and gender-based violence would not occur at the rates it does. If it prevented this violence, 40% of cops would not self-report that they have committed domestic violence.

This survivor was not the only person punished by the court when she was held without bail after defending herself in Baltimore City. Her entire family and community, especially her children, are also being punished. And in other hearings where a survivor is charged for defending themselves, the State’s Attorney’s Office echoes the same arguments of a “volatile” situation, and the response is to hold another survivor without bail. The only thing that can be counted on in a criminal proceeding is that police and prosecutors often do more harm than good by punishing survivors of trauma and violence.

Justice in this case would be making sure that domestic and sexual violence never occur again. There are as many practices on how to confront sexual and domestic violence as there are survivors of that violence. Kaba puts out a call to “reject and remake an unjust criminal legal system that punishes survivors for the act of surviving.” We need to prioritize and support survivors at every turn, intervening when gender-based violence happens, and working to stop it altogether. The website Million Experiments explores snapshots of community-based safety strategies that can be learned from and put to use; the website encourages people

to work together to keep each other safe. One of these methods of interrupting domestic violence is safety planning, which, according to Community Justice Exchange, is the process of identifying risks, mapping out resources, and assessing options in order to increase safety for people surviving abuse. Safety planning can be done by anyone in community with survivors, as it is a relational strategy that involves listening to the survivor’s needs.

Another way to support survivors of violence being prosecuted for self-defense is through participatory defense campaigns, which are organizing models communities can use to transform power in courtrooms and impact case outcomes.Thanks to a powerful participatory defense team, Alexander was finally freed in January 2017 and, after seven years of confinement, was reunited with her children and family. No one should be jailed for defending themselves against gender-based violence, and if those in power continue to lock up survivors, communities will continue to show up and free our friends and neighbors. Victims and survivors deserve safety and care, not criminalization. We hope that well before her trial goes forward next year, the

survivor Hong ordered to be caged will be free from the violence of both her abuser and the state.

July 2022 Data

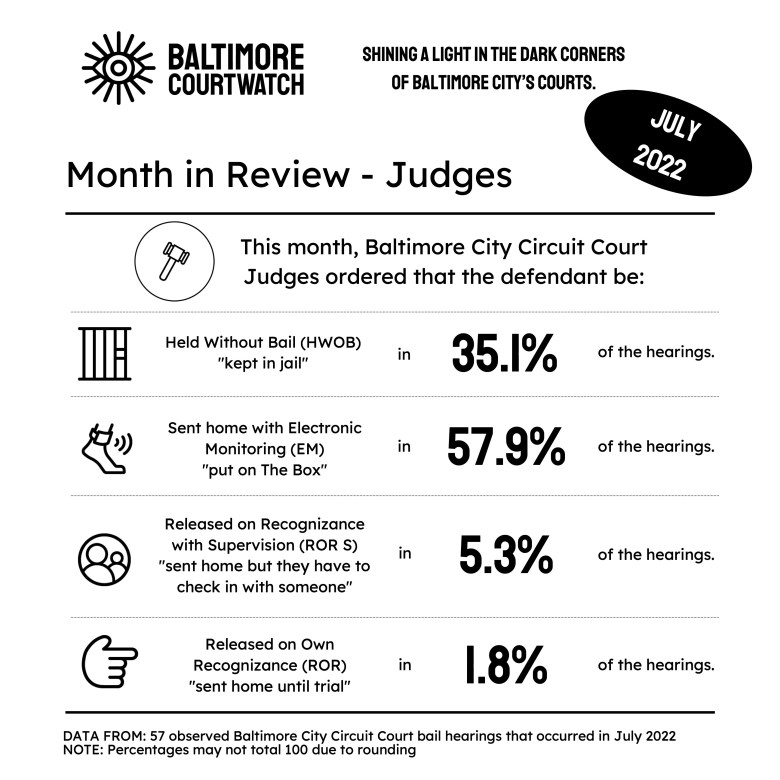

In the 57 hearings we observed in July 2022, prosecutors asked that the defendant be held without bond (HWOB), meaning kept in jail until their trial, in more than two out of every three hearings, or about 68 percent of the time. In more than 10 percent of the hearings, the prosecutor did not even show up. One hearing on July 1, two hearings on July 15, two on July 26, and one on July 29 had no prosecutor present at the hearing.

In those same 57 hearings, judges ordered the defendants to stay in jail until trial in more than one-third of the hearings (35.1 percent). When we examined the data at the individual judge level, we found that judges have different rates of ordering HWOB. Judge Jeannie Hong ordered HWOB in 50 percent of their trials and Judge Phillip Jackson ordered the same in 31 percent of their hearings. The Cornell Law School Legal Information Institute describes judicial discretion as “a judge’s power to make a decision based on their individualized evaluation, guided by the principles of law. As evidenced in the data, judicial discretion is alive and well in Baltimore City Circuit Court bail hearings.

(By Elaine Millas of Baltimore Courtwatch)